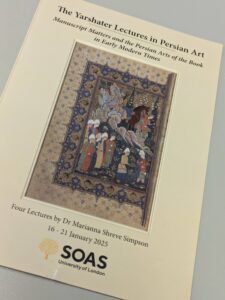

In January 2025, our recently joined team member Yih-Chuen Liao was pleased to attend the 2025 Yarshater Lectures in Persian Art at SOAS, London. This year, Dr. Marianna Shreve Simpson was invited to give four lectures on the arts of the book. While discussing the typologies of page markers in one of the talks, Dr. Simpson introduced many forms of page markers in Persian manuscripts, including the use of recycled and trimmed decorated paper, and cited the work of Dr. Jake Benson, on this so far often neglected topic. Dr. Simpson presented meticulously researched materials and generously shared her recent findings, which will soon be published in her upcoming book. We look very much forward to reading her book!

While in London, Yih-Chuen took the opportunity to visit the temporary exhibition “A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang” at the British Library. The exhibition narrates multi-lingual and multi-faith life in medieval Dunhuang, an oasis town in today’s northwest China at the crossroads of flourishing historical East-West exchanges. In the 7th century, Dunhuang became a major center for Buddhism, and numerous works on paper of extraordinary quality were preserved. It was exciting to see two significant centerpieces of the exhibition that greeted visitors at the gallery entrance.

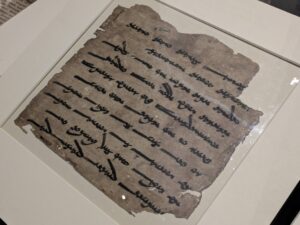

The first was a fragment from around the 9th century of the Avesta prayer Ashem vohu written in Sogdian transliteration, which testified the practice of the ancient Zoroastrian religion by Sogdians, who were Iranian people originally from Transoxciana in present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and traveled and later settled between China and Byzantium for trade. This fragment is the earliest surviving Zoroastrian scripture in the world, and it predates any other extant Zoroastrian manuscript by at least four hundred years.

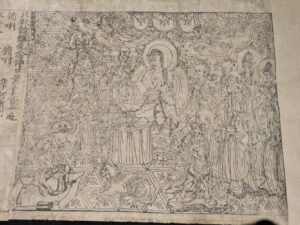

The second was the earliest dated complete printed book in the world, a copy of the Buddhist Diamond Sutra in Chinese from 868 A.D., found in the Library Cave (Cave 17) in Dunhuang. The frontispiece of this Diamond Sutra had an exquisite woodblock print image of the Buddha teaching in Jetavana, a holy monastery (vihara) in present-day Uttar Pradesh state in northern India. The final dedication of the manuscript further named Wang Jie (王玠), who sponsored the sutra printing for the merits of his parents, and documented the exact date of production – on April 15 in the ninth year of the Xiantong (咸通) reign during the Tang dynasty, which corresponds to May 11 of 868 A.D. It is tempting to think that the diamond sutra was produced around this time of the year precisely 1157 years ago!

The exhibition also displayed a paper stencil of a Buddha figure from the 9th-10th century. The Buddha’s outline was laid out with prick holes on the paper, which would allow an easy transfer of the motif to other surfaces by using color to trace the contours. This technique is often used to decorate manuscript borders in medieval Persianate worlds. In Dunhuang, the stencil was used to reproduce the image of the Buddha that would decorate the ceiling of caves. Another highlight in the exhibition featured a paper-cut flower made with decorated Chinese paper from the 5th-10th century, found in the Library Cave (Cave 17) in Dunhuang. This object was discussed in Dr. Jake Benson’s recent dissertation in the context of early Chinese decorated paper and its relation to paper marbling in early medieval China and later in the Persianate worlds.

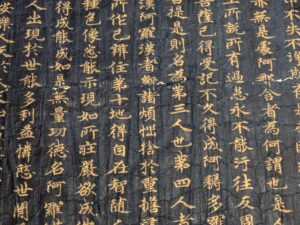

There was also a lavishly embellished fragment of the Great Parinirvana Sutra, written with gold ink on indigo-dyed paper from the 9th-10th century, also from the Library Cave. The color combination of indigo and gold can also be seen in the so-called Blue Qur’an made with parchment folios, produced possibly around the same time in the Islamicate worlds.

Finally, a wood pen from Miran, an abandoned oasis town site on the southern rim of the Taklamakan desert, caught the attention. This pen was dated to the 8th-10th century during Tibetan rule, and it was made by cutting the dried wood at specific angles for the desired scripts. The shape and production of the pen resemble that of a qalam, a pen made of reed, used for Islamic calligraphy.

The exhibition’s variety of decorated paper and scribal tools from early medieval East Asia and Central Asia attests to the development of decorated paper. It enables us to approach how these examples can be considered in relation to the later usage in the late Persianate worlds. Learning about the materiality of writing and papermaking from the Dunhuang exhibition at the British Library was truly intellectually stimulating. Yih-Chuen would like to thank Mélodie Doumy, the lead curator for Chinese Collections at the British Library, who she happened to have run into onsite while visiting the show, for organizing such a fascinating exhibition!